Opportunity to explore the buried past of Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site

History Underground

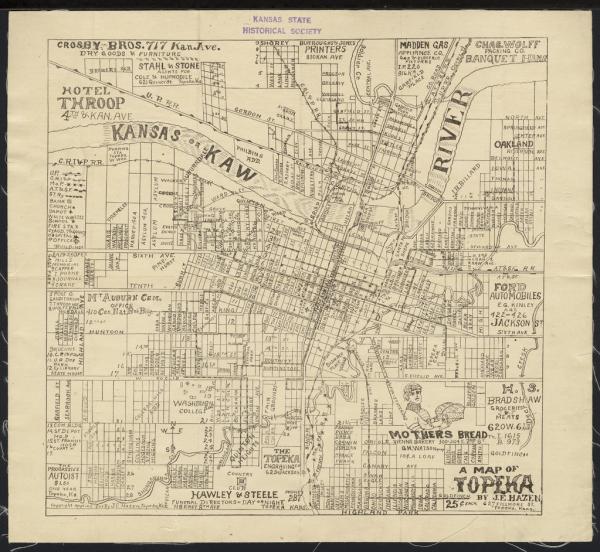

Image of Monroe Elementary School from 1927-1929 | Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/9338

People from all over visit the Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site in Topeka, to learn about the fight to end legal segregation in schools and the fight for equality during the American Civil Rights Movement. You may have visited this site, but did you know that the building you visited, called Monroe Elementary School, was not the first school building on the property? What if I told you that under the ground, the remains of multiple houses, outhouses, and an earlier school building are buried? This June, the public has the opportunity to explore the buried history of this incredibly important site, by participating in an archeological excavation on the property. This project will explore the site’s history prior to the 1954 Supreme Court Case was decided, as far back as the founding of Topeka. Here is a brief look at that history:

On the Banks of the Kansas River

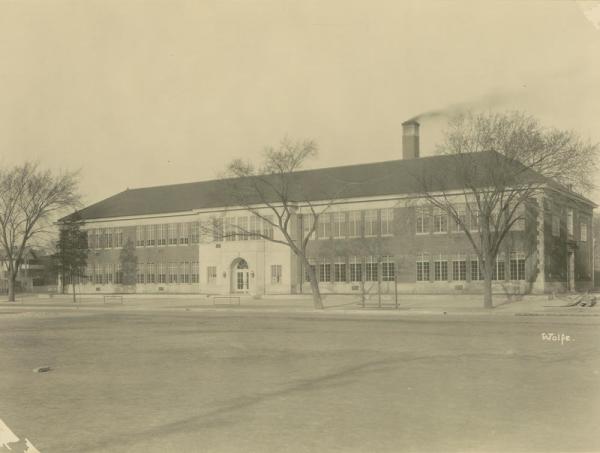

Early map of Topeka from 1900-1910 | Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/226357

Six months after the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in May 1854, nine men, all opponents of slavery, met on the banks of the Kansas River to draft an agreement creating the Topeka Association, hoping to create a free state community. The following year, abolitionist and free stater John Ritchie moved to Topeka, buying 160 acres of land, an area later called the Ritchie Addition or Ritchie Tract. Ritchie was involved in the underground railroad’s goal to end slavery in America and fought in the Union Army during the Civil War. By the 1880s, Ritchie had sold much of this land to formerly enslaved individuals who came to Topeka, and census records from this time show that many of South Topeka’s residents were African American. One of the neighborhoods within Ritchie’s Addition, Monroe, had a school constructed between 15th and 17th Streets along Monroe Street. Early maps of the school property show several outbuildings and other structures. Increased enrollment in the mid-1920s led the Board of Education to construct a new school, Monroe Elementary School, just south of the 1874 school building, which was later torn down.

At the time the original Monroe School was built, state law allowed but did not require schools to be segregated by race. However, after the end of the Civil War, attitudes toward segregation hardened, and schools separated students by the color of their skin. The Monroe School was one of four segregated Topeka Public Schools that African American children could attend in the city.

Separate is Not Equal

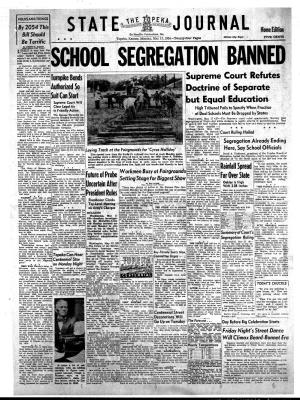

Front page of the Topeka State Journal on May 17, 1954 | Photo credit: https://www.kansasmemory.org/item/415

In 1879, the Kansas legislature passed a statute specifically allowing cities, such as Topeka, to operate segregated primary schools. From 1881 to 1949, the Kansas Supreme Court became an early venue for the constitutional question of segregation in public schools, with 11 cases being organized by African American parents across Kansas. Eventually, the Topeka chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) agreed to challenge the separate but equal doctrine that had been decided in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). A class-action suit was brought against the Topeka Board of Education by several Topeka families in 1951. Oliver Brown was the lead, and only male plaintiff in the case, whose daughter, Linda Brown, attended Monroe Elementary School.

Although the Kansas Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Board of Education, the case paved the way for a U.S. Supreme Court appeal. Five NAACP cases were combined under the heading of Oliver L. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision that the separation of children in public schools based on their race was a violation of the 14th Amendment and therefore unconstitutional. The following year, the Court directed the country to implement its decision "with all deliberate speed.” Despite the rulings issued by the Supreme Court, schools across the country were slow to desegregate, leading to increased tension across the Nation and the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Commemorating the Fight for Equal Rights

The National Historic Site today. | Photo credit: Preston Webb, National Park Service

Due to declining enrollment and substandard facilities, Monroe Elementary School closed its doors in 1975. Over time, the school building was modified, and then bought and sold multiple times between 1980 and 1991, when it was purchased by the Trust for Public Land. The property was designated as a National Historic Landmark later that year. On October 26, 1992, the building and grounds were designated as Brown v. Board of Education National Historic Site, with the property being transferred to the National Park Service a year later. After renovating and updating the school building and property, as well as adding exhibits focused on the Supreme Court Case and the Civil Rights Movement, the site was opened to the public in 2003.

Join Us This Summer at the Kansas Archeology Training Program Field School

Participants excavating during the 2019 KATP field school. | Photo Credit: Sue Smith, Kansas Anthropological Association

Every year, the Kansas Historical Society and Kansas Anthropological Association offer the Kansas Archeology Training Program (KATP) field school, which is an opportunity for the public to work alongside professional and avocational archeologists on an excavation. The 2022 field school will partner with the Brown v. Board of Education Park, and the National Park Service’s Midwest Archeological Center (MWAC) and focuses on further exploring the early history of the Monroe School neighborhood and early Topeka. The field school is June 3 - June 18, 2022, but is closed on Mondays. Participants will be able to set their schedule to either participate in excavation at Brown v. Board or to work in the archeology lab at the Kansas Historical Society.

The goal of the 2022 KATP is to expand on knowledge of the school property from the early years when it was purchased by John Ritchie in 1855 and up to the 1954 Supreme Court decision. The field school will be an opportunity to explore structures buried on the property that once stood near the earlier Monroe School. Little information is known regarding the preservation of these structures. Through the use of archeology, we can gain a better understanding of those who lived in the Monroe school neighborhood. This project will help tell of the crucial time between the Civil War and the Civil Rights eras, which profoundly impacted people’s lives throughout the nation. Research goals will be shaped by input from the National Park Service to assist them in telling this story and gaining more understanding about the community that surrounds this property.

No experience is required—just a desire to learn about history. Volunteers can attend for a few days or the entire field school. Participants must be at least 12 years old, and children aged 12-17 must be accompanied by a parent or sponsor. Participants are charged a small registration fee to help cover the costs of the project. Online registration is open from March 1-May 31, 2022. Registration is limited per day and will be taken on a first-come, first-served basis. You can find out more about the field school, including how to register, by visiting the Kansas Historical Society’s webpage for the project: https://www.kshs.org/katp.