"If they had had some encouragement, it might have worked."

It was an idea that almost made the names of William J. Purvis and Charles A. Wilson, both of Goodland, synonymous with the helicopter. But, born almost 30 years before that word was first used, and lacking encouragement and financial backing, Purvis' and Wilson's "flying machine" died almost as it was born.

The two Rock Island machinists built the first rotary wing aircraft to be patented in the United States in 1909. They claimed that this would be "an airship unlike any form of aircraft ever invented or constructed. This aircraft will go up or down perpendicularly, stop at any given point of elevation, land or start anywhere and can be steered or propelled in any direction."

Purvis and Wilson proposed to use the machine in the light transportation business or in making observations. It would be ideal for doing so for it would be constructed so that it could be brought as close to the ground as necessary to deliver or receive mail or parcels and then ascend without making a landing. It would be able to assume a steady position at any height.

The men began with models, constructing them in their workshop near the Rock Island roundhouse in Goodland. They discarded the working model after the working model as unworkable.

Finances soon became a problem and, in an attempt to raise needed funds to continue the project, the two inventors offered their idea to the Goodland community in the form of the Goodland Aviation Company. Stock sold at $10 per share. There were few takers, however.

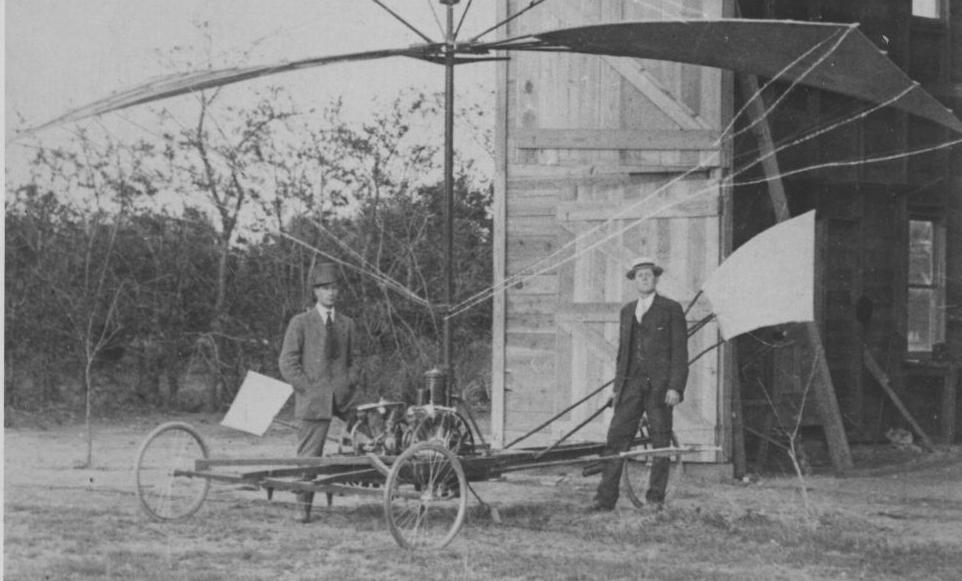

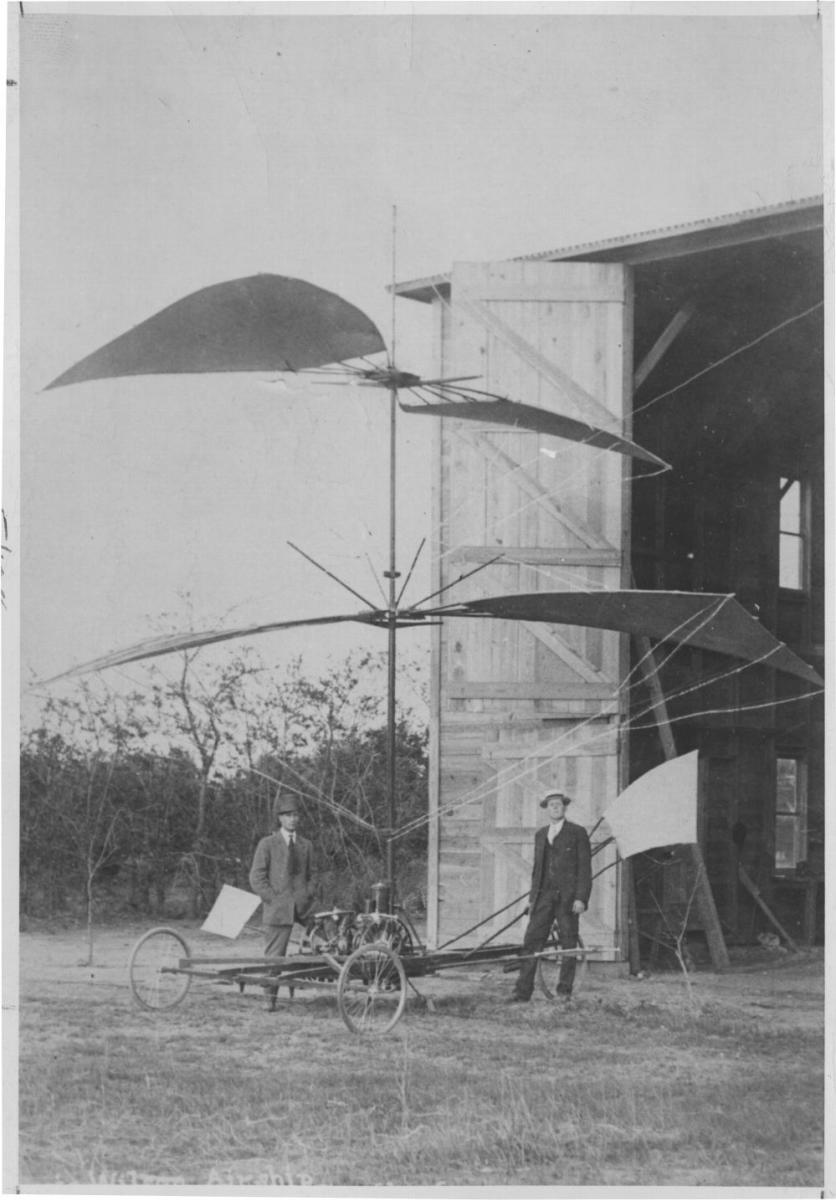

Thus, on Thanksgiving Day of 1909, Purvis and Wilson staged a demonstration of a model craft. A large crowd assembled at Purvis' home in the southwest part of Goodland. The machine Purvis and Wilson presented was a triangular craft which was powered with a belt hooked to a steam engine.

The flying machine was tethered to the ground but when power was applied it rose several feet off the ground. The flight lasted over a minute and, as the power was gradually shut down, the machine came to a gentle and controlled landing.

After the demonstration, there was great demand for stock in the Goodland Aviation Company. During the next three months, hundreds of shares were sold and speculation was that the shares would soon be worth $100 each.

Purvis and Wilson used the funds from the stocks to purchase two 50-pound, seven-horsepower Curtiss aircraft engines and a large stationary steam engine. They built a small machine shop and a large vertical hangar. They quit their railroad jobs and devoted all their time to perfecting what was now known as the Purvis-Wilson flying machine.

The machine next brought before the public was a self-powered model, powered by the two 50-pound, seven-horsepower Curtiss aircraft engines.

The crowd that gathered to see it launched in June of 1910 was large. A festive air prevailed. Undoubtedly some came in the hopes that they would see the machine crash. Supporters of Purvis and Wilson, however, held their breath expectantly, hoping that this launch would become as famous as that in Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903, when the Wright brothers first successfully flew their airplane.

World renown was not to be a part of this day, however. Purvis applied power without success. He added additional power with no results. Finally, he applied full power which did launch the flying machine. But full power was also too great for the light craft. It was tom apart in the air.

Purvis and Wilson then tried to rebuild the flying machine. By July, they had repaired the damage and were conducting tests with a stationary engine.

Dissension began to tear at the foundation of the Goodland Aviation Company. Some claimed that the overhead wings would provide the necessary poise in the air but forward propulsion would have to be provided with propellers as in the famed Wright brothers machine.

Purvis, however, contended that the forward movement could be obtained by tilting the rotor. When the investors insisted that he abandon this theory and implement the other, he left the Goodland Aviation Company and the town of Goodland. Wilson soon followed.

The Goodland Aviation Company folded not long after. Assets including the original model, the Curtiss engines, the hangar and machine shop were sold at auction. The buyer was John Keenan, one of the original investors. He purchased the materials for $700.

When John Keenan died, the patent for the rotary wing aircraft was found among his papers. Some Goodland citizens began discussing restoring the machine as the first helicopter in the U.S. Making a replica of the Purvis-Wilson flying machine to be housed in the Pioneer Museum became a Bicentennial project for Goodland.

The man selected for the task was Harold Norton, of Brewster, who was known throughout the area as a talented machinist, an individualist, and an inventor in his own right.

Norton had heard about the Goodland helicopter ever since he moved to the Goodland area in 1948. He had recently become interested in the history of engines. "I kind of like that sort of thing," Norton explained why he accepted the job of building the replica. It was a mind-boggling task. The patent issued in July of 1912 was vague and confusing. Written information was scant, verbal recollections almost nonexistent.

Every piece had to be manufactured by hand. The clutch alone is comprised of more than 16 pieces and took over 50 hours of machine work. Norton built the replica in his machine shop in Brewster. He spent hours and hours working on it, hours that became years.

Norton's biggest problem in constructing the replica was in keeping himself from correcting the mistakes that Purvis and Wilson had made ... to try to get it to fly. Norton constructed the flying machine so that those visiting the exhibit can push a button and watch as the four blades move laterally through the air.

The machine is now on exhibit at the High Plains Museum in Goodland. Basically, it is completed. Norton would have liked to put the two motors that powered the original flying machine on the replica, however. He has located one and believes it will eventually be donated to the museum. The other is in Topeka.

Norton leans over the iron railing, looking down at the machine he made. He reaches out a hand and pushes the button, activating the flying machine. The motor whirs softly. The four bamboo-covered blades slowly circle above.

"If they had had some encouragement, it might have worked," he says almost in a whisper.